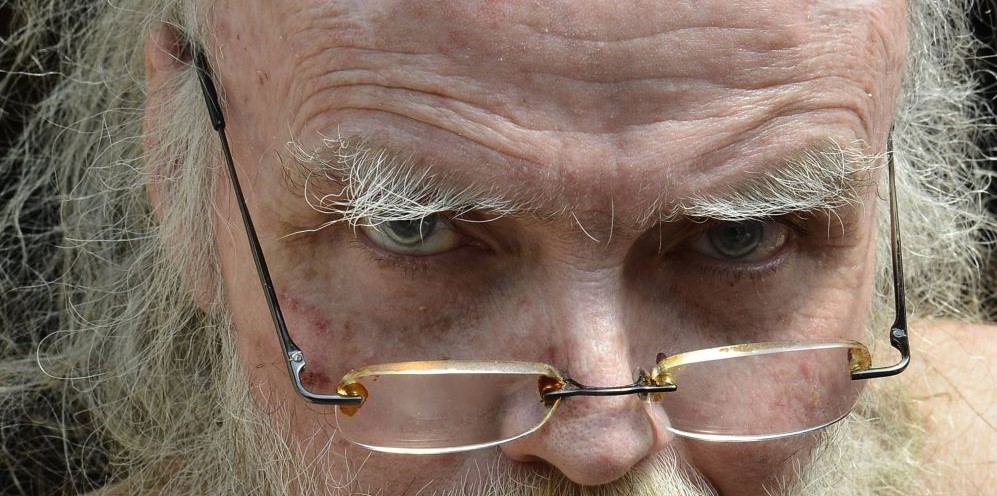

Eric Arthur Blair

For those of you who have read my bio on the About page here on my blog, or on my Amazon or AuthorsDen pages, you will know who my literary heros are.

Let us start with Eric Arthur Blair, or for those who don’t know him under that name, perhaps you may know him by his pen name – George Orwell. Eric was born in Motihari, in Bihar, India on the twenty-fifth of June 1903, the product of an English father and a French mother.

Eric was a novelist, essayist, journalist and critic. The fact that because of his scholastic achievements meant that he won a place as a King’s Scholar at Eton, did not mean that he ever considered himself as one of the so-called ‘elite’ in society. Far from it in fact. Because of his family’s social standing as well as the fact that Eric’s grades at school weren’t sufficiently high enough to ensure that he gained a place in either Oxford or Cambridge universities, his father chose his son’s career. Like him Eric had a love of the ‘East’. So it followed that he became an officer in the Imperial police, the forerunner of the Indian Police Service. Back then your father’s word was law.

Blair began his career in Burma. Needless to say Eric soon impressed his superiors, and was promoted to Assistant District Superintendant at the end of 1924. Posted to Syriam, close to Rangoon, he was now responsible for the security of two hundred thousand people.

By now Eric had earned the dubious reputation of being an ‘outsider’. His environment, along with the way the Burmese were being treated by his own countrymen was the catalyst for the direction his life would take. He wrote that he felt guilty about his role in the work of empire and he “began to look more closely at his own country and saw that England also had its oppressed …” Eric resigned his commission and headed back to England to his parents home in Southwold, not too far away from where I live here in the English county of Suffolk, before eventually settling in London in 1927.

Following the example of his own literary hero Jack London, looking for inspiration Eric began ‘slumming it’ in the poorest parts of London. For a while he ‘went native’ in his own country, dressing like a tramp and making no concessions to middle-class customs and expectations. Out of this experience and others came his first novel Down and Out in Paris and London published in 1933; a stark portrayal of life at the bottom of society in the twenties and thirties.

For a while he took various jobs whenever they were offered to him. For a few brief years he taught in a couple of schools – a prep school for boys in Hayes, and Frays College in Uxbridge. But by now books and everything to do with them were fast becoming the main priorities in his life. Thanks to his maternal aunt Nellie Limouzin, he landed the position of part-time assistant in a second hand bookshop run by friends of his aunt. Out of his time there came his next novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying in 1936.

At some time during that year, it was suggested that because of the popularity of his first novel that he investigate the lives and social conditions of the downtrodden in northern England. From that came his next gritty novel The Road to Wigan Pier, published in 1937. Simply researching into the appalling poverty and conditions at the time, inevitably led to his being brought to the attention of the Special Branch, a division of Scotland Yard. Just like now, back then the establishment didn’t like it when the conditions of the ‘lower classes’ were brought to the attention of the world at large. In that regard nothing has changed…

By now the Spanish Civil War was gaining momentum. After marrying Eileen O’Shaugnessy, Eric headed to Spain like hundreds of others with a conscience to join the International Brigade to fight on the side of the common people against Franco’s facist backed military uprising.

Out of his time spent in the trenches at places like Aragon and later Alcubierre, 1,500 feet above sea level, inevitably came his next novel Homage to Catelonia. While thankfully there was not much fighting, the often freezing weather conditions at that altitude made their lives a misery. The lack of weapons, ammunition and in particular good boots meant that the time they spent there was almost farsical. The regular supply of both weapons and food was sporadic to say the least. Any form of medical help, even common pain killers as well as bandages and dressings, was unavailable in the front lines.

On many occasions to fend off their desparate hunger and the inevitable ilnesses brought on by being undernourished, they were forced to forage for what food they could find, often while being targeted by the opposition from the safety of their own trenches. Despite the risks, at least their excursions got them away from the permanent population of rats in their trenches and dugouts for a while. However, it didn’t put any kind of distance between them and their constant personal companions – body lice.

Eric returned to England in 1937 after recovering from being wounded in the throat. By now his views on the debacle that was the Spanish Civil War largely fell on deaf ears. No one in the establishment wanted to know.

At the outbreak of World War II, he was classed as unfit for military service. Determined to do his bit for his country, he joined the Home Guard. A quote from his wartime diary in 1941, sums up his thoughts at the time – “One could not have a better example of the moral and emotional shallowness of our time, than the fact that we are now all more or less pro Stalin. This disgusting murderer is temporarily on our side, and so the purges, etc., are suddenly forgotten.”

By now the idea of his next novel Animal Farm, eventually published in 1945, slowly began to form in his mind. While it is undoubtedly black humour, it is a clear portrayal of his deep loathing for Stalin and everything communism stood for at the time. The book struck a chord in the post war anti-communist climate with so many people, making him a much sought after writer and public figure.

Probably the work Eric is best known for is his anti-totalitarian dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four published in 1949, a year after I was born. But by then he had been diagnosed with incurable tuberculosis. He was to linger on until he eventually died on the twenty-first of January 1950.

To my mind, and those of many others; Eric was, and still is, the finest novelist of his kind. He didn’t just write, he lived each of his novels before putting pen to paper. What better way to collect everything a writer deems necessary for a literary masterpiece, or in his case several. We will never see his like again…

Thank you for sharing your thoughts on George Orwell. He is also one of my favourite authors.

LikeLike

No matter what some modern critics say about his writing style being dated, to me his books are timeless.

LikeLike

Sadly I’ve only read 1984 and Animal Farm – the latter had a major impact on my attitude to mental and physical bullies (I always squared up to them, even if I did lose sometimes, they never made any further attempts against me) and my automatic defence of ‘underdogs’ 😀

LikeLike

I’m reading Homage to Catalonia, a non-fiction novel, at the moment. Reading it I can fully understand Eric’s hatred for fascists and communists, not to mention how he felt about the Allies cosying up to Joe Stalin during the Second World War.

LikeLike

Hear, hear! We shall not look upon his like again but we sure as hell need someone like him to chronicle the world today.

LikeLike

Sadly I can’t see it happening in these days of television, radio and the internet, can you?

LikeLike

No, alas. And certainly not in a corrupt world which lacks any hint of integrity and shies away from the truth because it suits them. On a lighter note, it gives me pleasure to know that you live somewhere I’m very fond of although I don’t know the whole area that well. I’ve worked at Jill Freud’s summer theatre in Southwold a couple of times and visited some of the towns and villages around the place. And my aunt and uncle and one my cousins and his family live near Sudbury.

LikeLike

My hometown is nine miles inland from Lowestoft Sarah. 😉

LikeLike

I’m working out the co-ordinates now! Thanks so much for following First Night Design. I recently started a history blog (mostly re-blogs), which might interest you: http://firstnighthistory.wordpress.com

LikeLike

Also following – thanks 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you 🙂

LikeLike

My pleasure. After all its only fair since you have done me the favour of following mine. 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Have We Had Help? and commented:

Eric Blair esq…

LikeLike